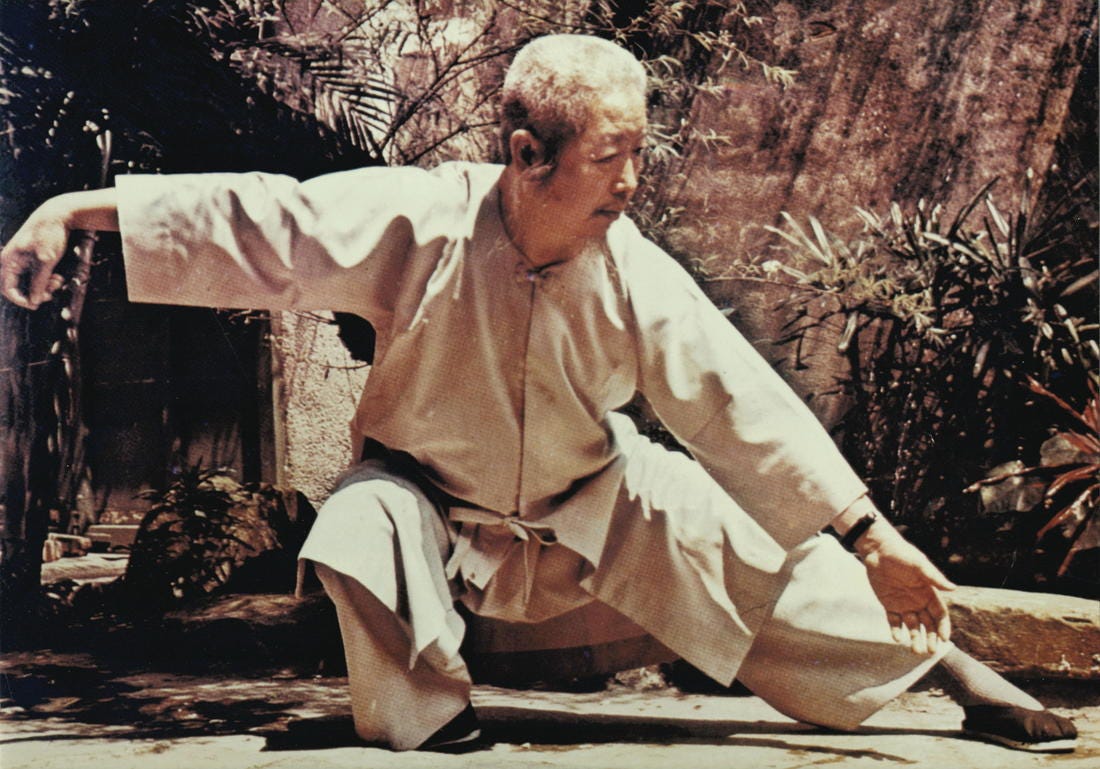

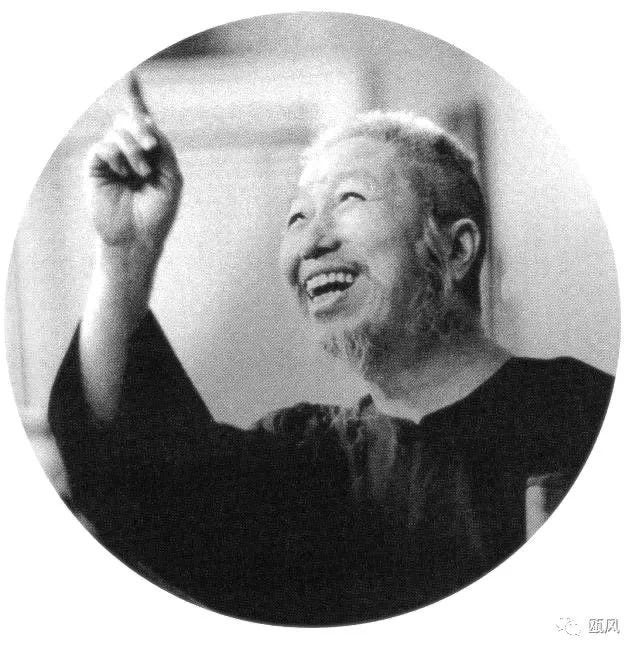

The Chinese Secret Of Investing In Loss (with Professor Cheng Man Ching)

REPAIRING A BROKEN WORLD | MARCH FEATURE III

I'd been practicing tai chi for ten years when I started training in tai chi push hands, not to mention having practiced martial arts since childhood. Despite this I found myself quickly humbled.

Push hands or tuishou is a two-person training routine that’s learned after the tai chi form. In push hands one person pushes and the other neutralizes their incoming force. Once this cycle is complete, the pair switch roles and this exchange goes back and forth in a flowing manner until a mistake is made. Either the pusher lands a successful push or the neutralizer empties the force and makes the pusher lose balance.

In the above video Professor Cheng Man Ching performs push hands with his students in Taiwan, 1953

When I tried to use force, I'd find myself falling over towards the ground, when I tried a clever technique, I'd be pushed by my teacher into a wall. It didn't seem to matter what I did, I was either flying off at great speed or falling over at great speed. "What do I do to win?" I'd ask my teacher. "Relax, more soft," was the answer then, and more than twenty years later, still the same now. "I am relaxed," I'd protest. "More relaxed,” he'd say. "Give up more."

In Chinese martial arts the expression chi ku (吃苦), means literally to eat bitter. The idea is, at its face value, to endure difficulty, to accept suffering when necessary. Chi ku goes hand in hand with expressions like, “first comes bitter, then comes sweet”(先苦後甜), the idiom that describes how hard work and sacrifice pays off. In our tai chi tradition, Professor Cheng Man Ching used a similar expression chi kui (吃 虧), meaning to eat loss, which in English is more colloquially translated as “invest in loss”. *

"Invest in loss" is a good translation of “eat loss” for Western audiences, as it emphasizes the long-term reward that comes from learning to lose in the short term.

"Therefore I say, 'To learn T'ai Chi Ch'uan, it is first necessary to learn to invest in loss.' When one learns to invest in loss, [the loss] will polarize into its opposite and be transformed into the greatest profit."

餘故日,學太極拳必自學吃虧始。從來學拳,無不欲勝人而佔便宜者,今日學吃虧,誰寧為之。

-Cheng Tzu's Thirteen Treatises on T'ai Chi Ch'uan by Cheng Man-ch'ing, translater by Benjamin Pang Jeng Lo & Martin Inn.

I remember I once heard an interview on the radio with a spiritual teacher running workshops in Rumi’s poetry. When the interviewer asked him how he could choose what to teach when there was such a large body of material, he replied that it wasn’t difficult, if the teaching is true, you could just take one idea that resonated with you and go deep. “Take for instance Jesus Christ’s idea that we should love one’s neighbor as oneself. That’s a whole life philosophy, what more do you need? You can work on that for a lifetime.” I was moved by the clarity of his insight and later, as I studied Professor Cheng’s tai chi and his Confucian and Taoist philosophy, I remembered those words and thought the same could just as easily apply to the concept “invest in loss”.

“The Taoists advocate wu wei (non-action or effortlessness) and the Buddhists venerate “emptying.” The motto for T’ai-chi practice must be “investment in loss.” It is what Confucius meant by k’e chi—to subdue the self. How is this manifested in mundane affairs? It means to yield to others, thus quashing obstinacy, egotism, and selfishness. But it is not an easy thing. To persist in the Solo Exercise amid life’s busy requirements is self-humbling. In the Pushing-Hands Practice, the student must accept failure many times over in the early stages. To yield and adhere to an opponent cannot be achieved by an egotist—his ego will not tolerate the bruisings necessary before mastery comes. But here, as in life, this proximity to reality must overcome ego if one is to walk a whole man.”

-T'ai Chi: The "Supreme Ultimate" Exercise for Health, Sport and Self-Defense” by Cheng Man-Ching.

To compare the pinnacle of Taoist and Buddhist practice with the tai chi motto "invest in loss", gives you a sense of how deep the teaching runs.

To understand the concept of investing in loss, we need to familiarize ourselves with the yin-yang symbol (called the taijitu in Chinese, or ““the tai chi digram").

yinyang: in Eastern thought, the two complementary forces that make up all aspects and phenomena of life. Yin is a symbol of earth, femaleness, darkness, passivity, and absorption. It is present in even numbers, in valleys and streams, and is represented by the tiger, the color orange, and a broken line. Yang is conceived of as heaven, maleness, light, activity, and penetration. It is present in odd numbers, in mountains, and is represented by the dragon, the color azure, and an unbroken line. The two are both said to proceed from the Great Ultimate (taiji), their interplay on one another (as one increases the other decreases) being a description of the actual process of the universe and all that is in it. In harmony, the two are depicted as the light and dark halves of a circle.

The reason we need to understand yinyang in order to understand investing in loss is because loss falls into the category of "yin", and when we speak about the rewards of investing in those negatives, we are talking about "yang".

With tai chi, we invest in loss by continuously losing to the opponent (yin) while trying to become softer and neutralise better until the opponent is imbalanced, falls over and we have won (yang).

Video: Eastern philosophy teacher Alan Watts explains the tai chi (yinyang) diagram.

Now that we understand yin and yang we can start to look at real-world examples of investing in loss.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Beautifully Broken to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.