What is it about Brautigan's library that is so appealing? A place that is both in and not in the world. A place outside of time where different rules apply.

The Library

THIS is a beautiful library, timed perfectly, lush and American. The hour is midnight and the library is deep and carried like a dreaming child into the darkness of these pages. Though the library is "closed" I don't have to go home because this is my home and has been for years, and besides, I have to be here all the time. That's part of my position. I don't want to sound like a petty official, but I am afraid to think what would happen if somebody came and I wasn't here.

I have been sitting at this desk for hours, staring into the darkened shelves of books. I love their presence, the way they honor the wood they rest upon.

I know it's going to rain.

Clouds have been playing with the blue style of the sky all day long, moving their heavy black wardrobes in, but so far nothing rain has happened.

I "closed" the library at nine, but if somebody has a book to bring in, there is a bell they can ring by the door that calls me from whatever I am doing in this place: sleeping, cooking, eating or making love to Vida who will be here shortly.

She gets off work at 11:30.

The bell comes from Fort Worth, Texas. The man who brought us the bell is dead now and no one learned his name. He brought the bell in and put it down on a table. He seemed embarrassed and left, a stranger, many years ago. It is not a large bell, but it travels intimately along a small silver path that knows the map to our hearing.

Often books are brought in during the late evening and the early morning hours. I have to be here to receive them. That's my job.

I "open" the library at nine o'clock in the morning and "close" the library at nine in the evening, but I am here twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week to receive the books.

An old woman brought in a book a couple of days ago at three o'clock in the morning. I heard the bell ringing inside my sleep like a small highway being poured from a great distance into my ear.

It woke up Vida, too.

"What is it?" she said.

"It's the bell," I said.

"No, it's a book," she said.

I told her to stay there in bed, to go back to sleep, that I would take care of it. I got up and dressed myself in the proper attitude for welcoming a new book into the library.

My clothes are not expensive but they are friendly and neat and my human presence is welcoming. People feel better when they look at me.

Vida had gone back to sleep. She looked nice with her long black hair spread out like a fan of dark lakes upon the pillow. I could not resist lifting up the covers to stare at her long sleeping form.”

“A fragrant odor rose like a garden in the air above the incredibly strange thing that was her body, motionless and dramatic lying there.

I went out and turned on the lights in the library. It looked quite cheerful, even though it was three o'clock in the morning.

The old woman waited behind the heavy glass of the front door. Because the library is very old-fashioned, the door has a religious affection to it.

The woman had a look of great excitement. She was very old, eighty I'd say, and wore the type of clothing that associates itself with the poor.

But no matter ... rich or poor ... the service is the same and could never be any different.

"I just finished it," she said through the heavy glass before I could open the door. Her voice, though slowed down a great deal by the glass, was bursting with joy, imagination and almost a kind of youth.

"I'm glad," I said back through the door. I hadn't quite gotten it open yet. We were sharing the same excitement through the glass.

"It's done!" she said, coming into the library, accompanied by an eighty-year-old lady.

"Congratulations," I said. "It's so wonderful to write a book."

"I walked all the way here," she said. "I started at midnight. I would have gotten here sooner if I weren't so old."

"Where do you live?" I said.

"The Kit Carson Hotel," she said. "And I've written a book." Then she handed it proudly to me as if it were the most precious thing in the world. And it was.

It was a loose-leaf notebook of the type that you find everywhere in America. There is no place that does not have them.

“There was a heavy label pasted on the cover and written in broad green crayon across the label was the title:

GROWING FLOWERS BY CANDLELIGHT

IN HOTEL ROOMS

BY

MRS. CHARLES FINE ADAMS

"What a wonderful title," I said. "I don't think we have a book like this in the entire library. This is a first."

She had a big smile on her face which had turned old about forty years ago, eroded by the gases and exiles of youth.

"It has taken me five years to write this book," she said. "I live at the Kit Carson Hotel and I've raised many flowers there in my room. My room doesn't have any windows, so I have to use candles. They work the best.”

“I've also raised flowers by lanternlight and magnifying glass, but they don't seem to do well, especially tulips and lilies of the valley.

"I've even tried raising flowers by flashlight, but that was very disappointing. I used three or four flashlights on some marigolds, but they didn't amount to much.”

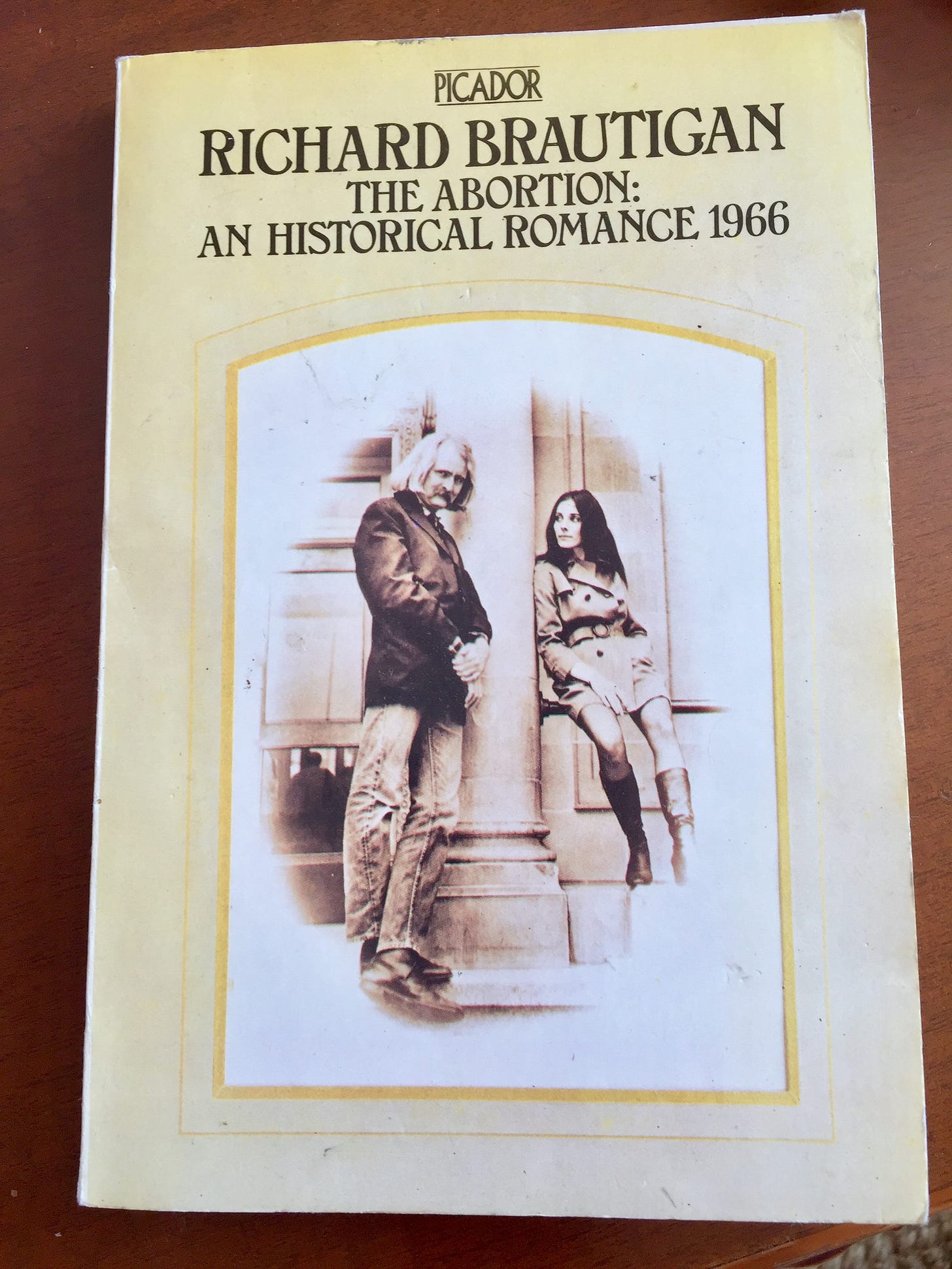

Richard Gary Brautigan (January 30, 1935 – c. September 16, 1984) was an American novelist, poet, and short story writer. A prolific writer, he wrote throughout his life and published ten novels, two collections of short stories, and four books of poetry. Brautigan's work has been published both in the United States and internationally throughout Europe, Japan, and China. He is best known for his novels Trout Fishing in America (1967), In Watermelon Sugar (1968), and The Abortion: An Historical Romance 1966 (1971).

Brautigan once wrote, "All of us have a place in history. Mine is clouds."