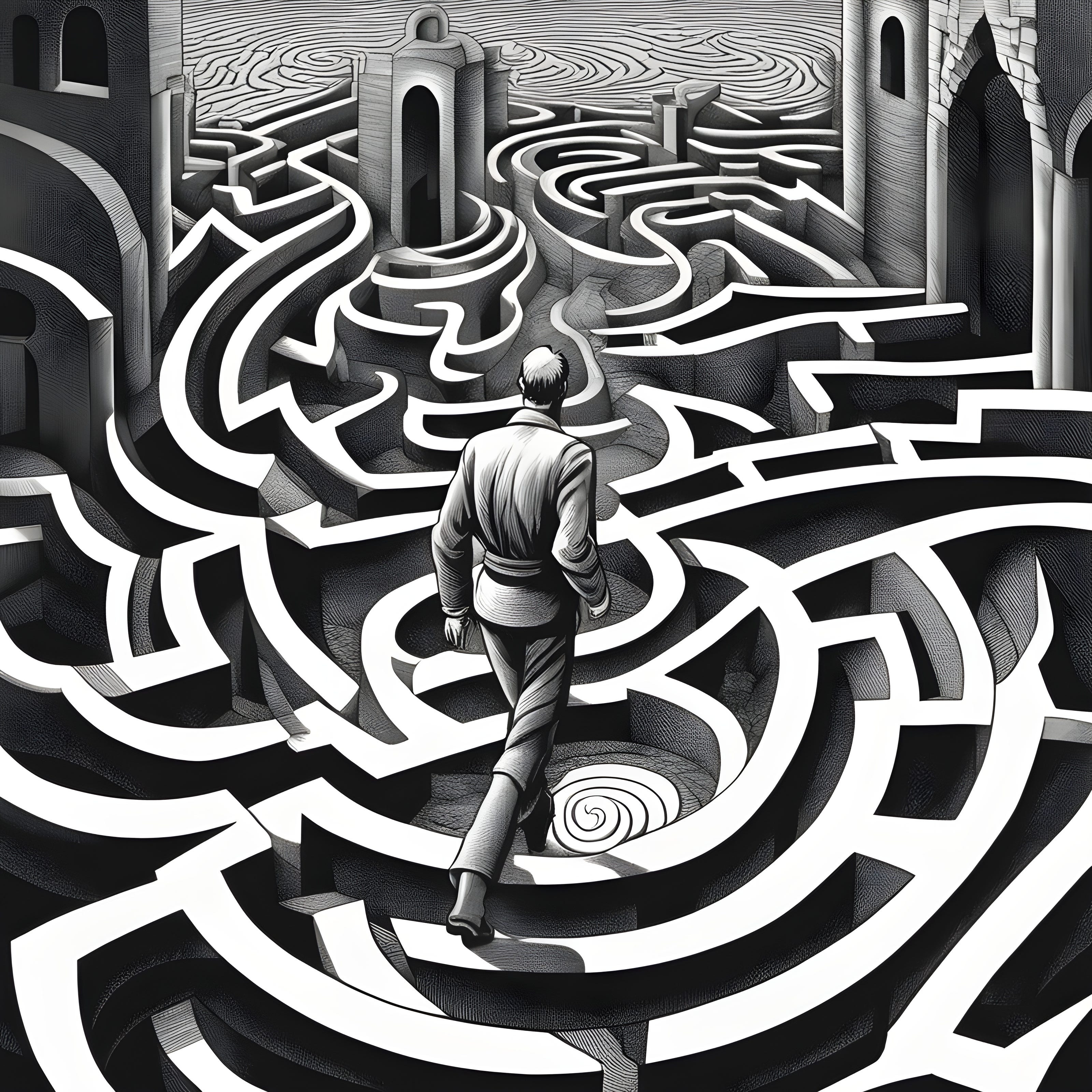

Into The Labyrinth (with Philip K Dick, The Monkey King, and Dante)

FICTION | FEBRUARY FEATURE I

Fifty years, most of it trapped in this dank labyrinth, sometimes awake, most of it asleep. Either way, time passes.

There was a time before the labyrinth. My body was a soft, sunlit ball, then a pliable, thoughtless sprite, and eventually a fleshy automobile, blooming in motion. This flesh vehicle feeds on the sacrifices of countless plants and animals.…