Beautifully Broken Issue #25: Peace Through Boredom

IDEAS, ART & WISDOM TO REPAIR OUR BEAUTIFUL WORLD

Happy Saturday! Welcome to Beautifully Broken Issue 25: Peace Through Boredom.

IDEAS: World Peace Is Easy If You're Boring

Who controls public discourse? Often it's the loudest voice with the narrowest interest. Focus and energy are effective in not only making oneself heard, broadcasting one's ideas to a larger audience, they are also appealing qualities which the media pick up on. A person with weak ideas but strong focus and energy is much more entertaining and engaging to broadcast than a person with good ideas but poor presentation. What about people with good ideas and focused energy? They're having a hard time too, as the public space is drowned out by extremists. What's an extremist? Someone who holds to a particular point of view with such conviction that given the chance they would force everyone else to comply with that point of view for ”their own good”.

I think most people are somewhere in the center, they are a little conservative on some issues (open crime in the streets is bad, a police force is necessary, we must punish criminals to deter crime) but overall a little liberal (let people live the lives they want to live as long as it doesn't harm others). So if most people are reasonable and not particularly interested in imposing their views on others, how has the world got into such a mess?

It seems that people with extreme positions have hijacked public discourse; they shape public policy and continue to drive the world towards wide-scale, ongoing conflict at great cost to the average person. How are they able to do that? Because the loud individual (and I mean loud not just in the auditory sense) is a lightning rod not just for the media, but also social media, and has become the model, the diet of personality, that a large, and mostly young, demographic of the global population is being raised on. People are competing to become the most loud in order to gain attention and status. In this context, loud political voices seem heroic, noble and exciting, where in actual fact they may simply be outright dangerous.

So what is the answer? The boring middle must reclaim its place in the discourse. The boring middle are the peacemakers, the people who don't want war or revolution and the price that both exact, they just want life to be peaceful, to minimize suffering, to raise families or live a happy single life, to find a reasonable compromise, resolve conflict and move on. They want a fair system delivered by an uncorrupted government that has the interests of its own people at heart.

Speak up for common sense, world peace and the boring middle, and don't feel corralled into picking a side. That is not to say that one side in any conflict can't be more virtuous than the other, in fact extremists bet their life (and yours) on measuring how much more virtuous their side is, but if there's no one talking peace then it's quickly forgotten, ruled out as an option.

It's much less exciting to see both sides of a conflict and cry for peace (although you'll get some excitement from extremists on either side of the conflict who will try to mark you as their enemy - for extremists you're either in or out, and anyone who is not with them is automatically the enemy, weak, confused, etc.), but that aside it's worth continuing to say, “I don't want to pick a side, I want to talk peace.” The boring middle doesn't need either side of a conflict to listen (and the more committed to an extreme position someone is, the less able they are to listen to anything but the message they're seeking empowerment through), all you need to do is be heard by other people of the boring middle who feel they have no voice, that they aren't represented in the media and aren't listened to by their politicians. Since the boring middle makes up the majority of the population, it wouldn't take much more than for everyone to whisper peace to make a giant wave of common sense that would wash away the need for conflict and make a great, tranquil sea of peace.

HEADLINE FICTION #10: Angel Fire

Here's a new format for short fiction that I've invented. It's a 70-word story in three panels with a pattern of 7-16-47 words, where the first 7 words form a headline style title, the 16 serve to fill out the headline information a little more and the final 47 contain the meat of the story and resolution. I think I'll call it "headline fiction". These micro stories of mine are based on dreams (and nightmares!).

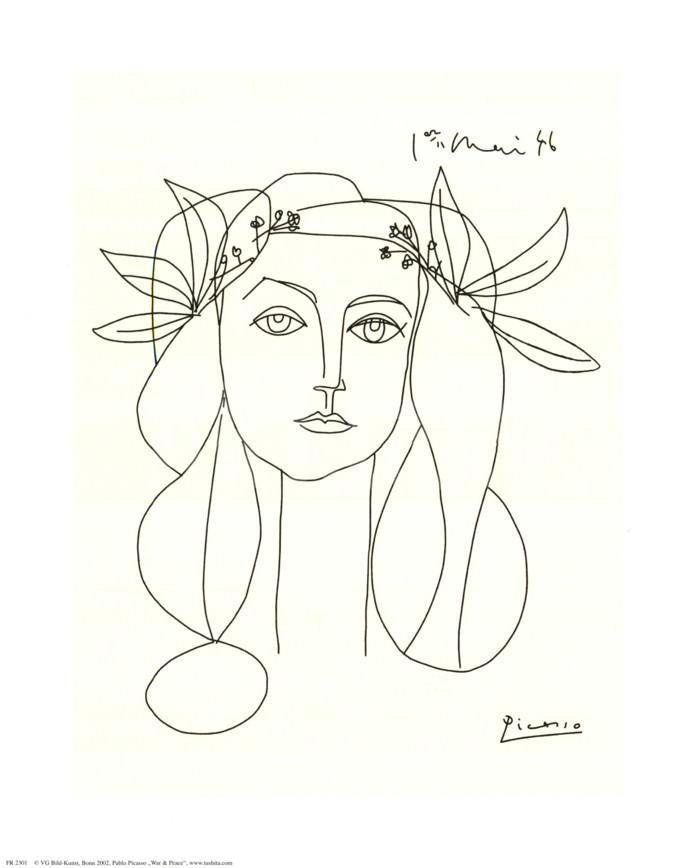

ART TO MEDITATE UPON

War & Peace (a single line drawing) by Pablo Picasso

What drives us to war? How do we envision peace? How much of our drive to force our position on others comes from genuine wisdom and how much from evolutionary biology? An animal need to expand territory, to claim material possessions, the need to project our fear onto others so we don't have to face it ourselves?

Perhaps it is Helen of Troy depicted in the drawing. Helen, thought to have been the most beautiful woman in the world, had many suitors, but she eventually married Menelaus. However, the goddess Aphrodite promised Paris that he would have Helen's hand in marriage, so he abducted her and brought her to Troy, starting the Trojan War.

In the sixteenth-century play Doctor Faustus , by Christopher Marlowe (a contemporary of Shakespeare) has Faustus say: “Is this the face that launched a thousand ships?” when the devil Mephistopheles shows him Helen of Troy.

WISDOM OF OTHERS

Excerpt from World Peace And How We Can Achieve It (Oxford University Press, 2019) by Professor Alex J Bellamy

“It isn’t enough to talk about peace. One must believe in it. And it isn’t enough to believe in it. One must work at it." —Eleanor Roosevelt, Voice of America broadcast, November 11, 1951

For as long as humans have fought wars, we have been beguiled and frustrated by the prospect of world peace. Like alchemists, we have searched in vain to unlock the secrets of peace. We have dreamed up extraordinary ways of cracking the code. In Ozgur Mumcu’s 2016 novel, The Peace Machine, the protagonist Calal Bey becomes embroiled in a shadowy plot at the turn of the twentieth century to build a machine that employs electromagnetism to manipulate human souls and turn all of humanity peaceful.

The enigmatic Sahir, apparently the plan’s mastermind, tells Calal that electromagnetism ‘is perhaps the most democratic force in the world. It exists everywhere in every single moment. It has the power to influence every single person’s soul’. But there’s a problem. The conspirators can’t generate enough electrical energy to give all humanity the peace treatment. So Sahir tells Calal and his allies that they must first free peoples from despotic and authoritarian rule. Only when people have liberty will the democracy of electromagnetism bring world peace, he tells them. Not until the adventure’s climax, where our protagonists find themselves at the palace gates disguised as circus performers during a coup in Belgrade, does anyone mention the obvious problem: to achieve world peace, they must eradicate free will. Yet even when Sahir points this out, our heroes barely think twice about switching on the peace machine. Sahir tries to stop them. The machine doesn’t work. It doesn’t bring peace; it sends people mad by stripping away their freedom. The only way we can have world peace, Sahir tells Calal, is if people decide that they want it. For that they must be free to make up their own minds.

Mumcu wasn’t the first to dream up a peace machine. In Bob Shaw’s Ground Zero Man, first published in the 1970s and then republished in 2011 with the title The Peace Machine, the technology had a quite different orientation. An unlikely hero, Lucas Hutchman, designs a device that can explode all the world’s nuclear warheads simultaneously. He writes to world leaders threatening to detonate the global nuclear arsenal unless they put an end to war. They refuse. With the world’s intelligence agencies on his heels, Hutchman gradually descends into a paranoia-driven madness.

Peace machines aren’t confined to the literary world. In 2018, school pupils visiting MOD, a ‘future-focused’ museum in Adelaide, Australia, were invited to design their own peace machine. Drones, the museum suggested, were a technology of war that could be converted into a peace machine. Pupils were invited to create others. Meanwhile, researchers at the University of Helsinki claimed that they were getting close to perfecting a peace machine: a machine learning tool to analyse speech that would help people build common meaning and avoid misunderstandings. Used this way, artificial intelligence could help us resolve our disputes peacefully. There is even a blues rock album called Peace Machine. Performed by Phillip Sayce, the musical peace machine seems no more promising than Calal’s electromagnetism. The album opens inauspiciously with ‘One Foot in the Grave’, and includes songs called ‘Sweet Misery’ and ‘Blood on Your Hands’. Perhaps Australia’s young inventors will fare better, but I doubt it.

For in truth there is no machine that can deliver peace. No equation to unravel. No hidden secret to uncover. It may be this realization that makes us so sceptical about the very possibility of peace, so cynical about attempts to think about what world peace might look like and how it might be achieved.

In his book on War and Conflict in Africa, Paul D. Williams suggested that understanding war was much like understanding cooking. Wars have different ingredients that are ‘cooked’ in different ways to produce different effects. Peace is the same. I think we know what most of the ingredients are. I think we are getting better at understanding the recipes that give us the most satisfying results—though there is still some way to go. But we remain unsure about whether we want to buy the ingredients and dedicate time to cooking. Other things seem more important, interesting, or alluring. Sometimes violence appears to offer quicker and easier ways of getting what we want. Sometimes violence in other parts of the world seems less important than the seemingly pressing issues right under our noses. As Sahir reminds us, ‘people have to decide whether they want peace or not’.

For more than a decade, I have dedicated my professional life to supporting the implementation of an international principle called the ‘responsibility to protect’. ‘R2P’, as it has become known, demands the protection of populations from the very worst of abuses—genocide and other atrocity crimes. I came to realize that we were not moving in the right direction; that unless things changed, the world my son would inherit would be one possibly even more violent than the one I had grown up in.

Last year, I took a train from London to Brussels. The trainline goes right through the battlegrounds of the First World War, where so many lives were lost. I crossed international borders once ferociously disputed without anyone even checking my passport. Looking out on the fields of Flanders, I was struck by what can be achieved when we put our hearts and minds to the cause of peace. But as my mind turned to Brexit, I was reminded that such achievements are always temporary, always contested. Peace is something for which every generation will have to struggle.

The urgent moral imperative to find solutions to the problem of war lay behind the endowment of the first academic Chair of International Relations, at what was then the University of Wales in Aberystwyth. It was for the express purpose of improving our understanding of war so that it might be prevented that David Davies endowed the Woodrow Wilson Chair in Aberystwyth in 1919. I had the privilege of spending three formative years there in the late 1990s studying for my doctoral degree. The first Professor appointed to the Woodrow Wilson Chair was Alfred Zimmern. Zimmern believed in the moral imperative of peace and in its possibility. So often nowadays unfairly cast as a naïve utopian, Zimmern was anything but. He understood that peace would have to be organized; that it would be achieved only if governments committed themselves to it. He was also painfully aware in the 1930s that most of the world’s most powerful governments were working against peace. Concerned by growing international discord, in 1934 Zimmern published ‘Organize the Peace World!’, an essay that challenged governments to build a better peace. It was a “powerful essay that levelled strong moral arguments about why peace matters and why governments should care about it with practical points about how that might be done. ‘War must be so effectively prevented as to eliminate it from the calamities to be reckoned with in the modern world’, he wrote. ‘That is to say, not only must war itself disappear, but the fear of war, and all that fear carries with it, must be eliminated also’. To do that, he argued, governments must be prepared to prioritize the common good, establish a collective system for the maintenance of peace, be clear in their purpose of preventing war and wholehearted in their support for collective measures, reflect their commitment to peace through domestic policies that promote the welfare of their peoples (Zimmern coined the term ‘welfare state’), and foster bonds of international cooperation in peacetime (Zimmern lobbied for the establishment of UNESCO and served as its first Secretary-General).

Both the moral urgency that Zimmern expressed in 1934 and the approach to peace he set out remain relevant today. So, I have taken a step back from the details of atrocity prevention policies to set out some thoughts about the larger questions of world peace. This book is the result. In the pages that follow, I will try to persuade you that world peace is possible and to encourage you to think about it more carefully, debate it more keenly, and pursue it more actively. We need to recover both the moral imperative for peace and the sober approach to its organization that Zimmern—and many other figures that we will meet in the following pages—embodied.

In setting out this case, I have been guided by G.K. Chesterton’s quip that ‘if something is worth doing, it is worth doing badly’. Striving for world peace, I think, is worth doing. I don’t pretend to have all the answers, or to be comprehensive, hence the ‘doing it badly’. What follows is simply my best effort to untangle some very difficult problems. Nor do I pretend to know what the destination—if there is one—looks like. What I hope, though, is that this book will encourage conversations and arguments about the possibility of world peace and how we might achieve it.

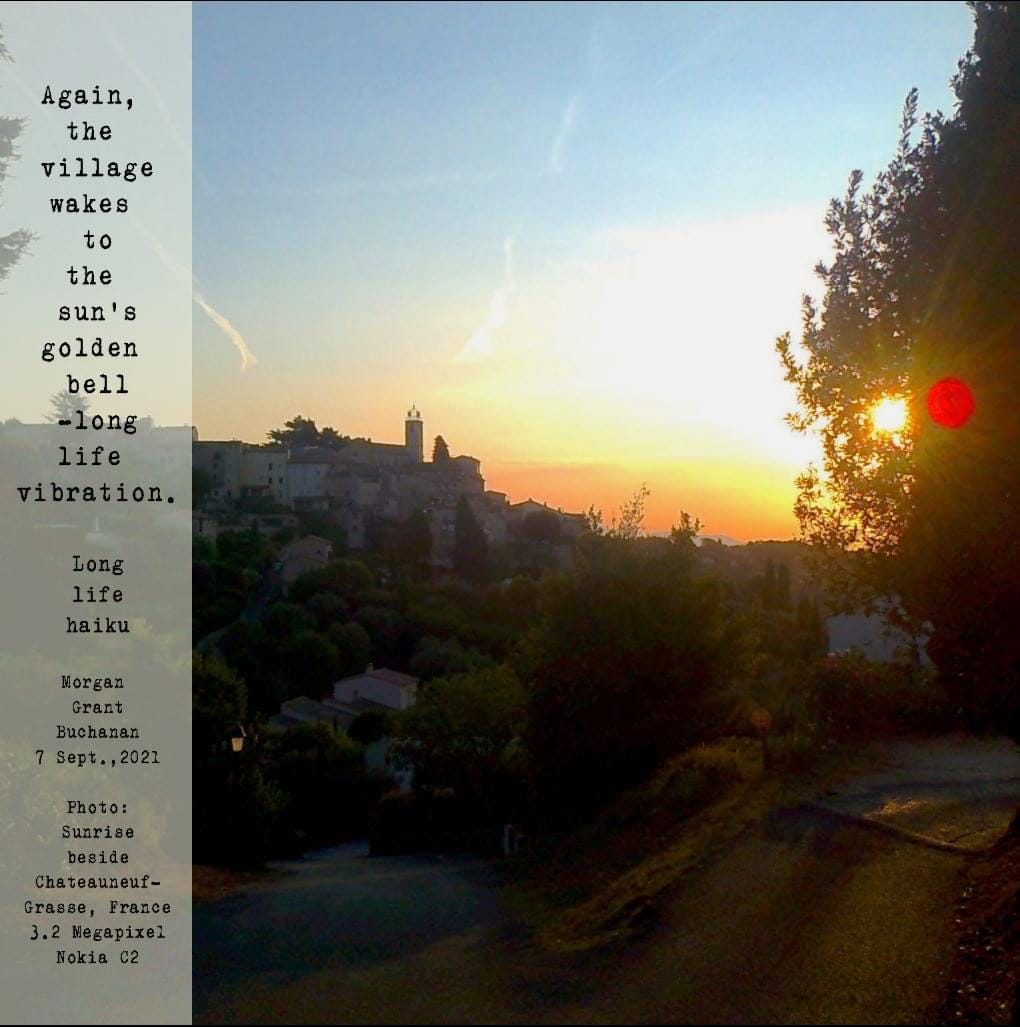

PHOTO HAIKU

Again, the village

wakes to the sun’s golden bell -

long life vibration.

Long Life haiku, 7 Sept.,2021

Photo: Sunrise beside Chateauneuf-Grasse, France 3.2 Megapixel, Nokia C2

Ideas To Live By In The Coming Week

If you were a moderate person and now find yourself pulled into the excitement of a popular cause, take a step back, relax, consider if you would better serve the world by doing nothing or promoting the idea of peaceful resolution.

The suffering of war goes on until one side defeats the other or both sides grow so tired of conflict and its human cost that they agree on peace. Better to maintain peace in the beginning. If the chance for peace is lost, find it again as quickly as possible to minimize suffering.

Most people just want a stable environment and a fair system to live in and build their lives. Will following a vibrant personality or strong political figure lead to this outcome for you?

Peace Now,

Morgan ,

7th September, 2024